-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Kimberly on ENGL 829 3/29 Reflection

- Nicole Hancock on ENGL 806 Timeline

- Jason Wise on Visual Ideology: Moving Beyond the Image

- Julia Romberger on Visual Ideology: Moving Beyond the Image

- Ruth Holmes on Paper #4 Theories and Methods

Archives

Categories

ENGL 820 4/12

When doing the readings for this week and thinking about the purposes of teaching as well as how to teach literature, I have to say I am just as confused as ever. How to teach literature, how to make the specialized languages and kinds of knowing visible to students is still an area I hope to research once I have the time. I am still unsure, first, what to identify as the specialized language as well as how to make accessible the types of attitudes and worldview literature is supposed to elicit. I’m quite sure the College Board’s special issue on “Reading Poetry” is not really teaching the specialized languages of poetry, but is instead providing examples of teaching activities, which could most likely be applied to other content-knowledge and do not have to do specifically with the intricacies and concerns of teaching poetry. I find it difficult myself to justify the teaching and study of literature given our economic and cultural environment. If anything, literature might inculcate students into the attitudes and dispositions valued in the professional world. I do see the significance of teaching cultural studies as a foundational course, if that course provides students with the ability to critique and think more deeply about popular culture and the media.

Posted in Uncategorized

ENGL 820 4/5 Writing Center Pedagogy

Writing centers have always been a mystery to me. I am uncertain if I have ever even stepped foot in one. I’ve always found this sort of interesting, considering my research and work focuses so much on writing. From reading writing center literature and talking to writing center specialists the main thing I have picked up on is the writing center is its own unique culture. Now I am not sure what this culture really is, but there certainly seems to be one. It seems as though this culture provides a nurturing environment for students to go, a liminal space between the class and home to get different types of support and feedback that you wouldn’t from the classroom. Since this culture tends to be positive and beneficial, what I see as the main concern writing center pedagogy should address at this point is gaining a more functional, responsive, and explicit approach to language. While “process,” as North discusses in “The Idea of a Writing Center,” was an important step away from formalism at the time, the relativist, social constructivist approach to writing that mainstream writing pedagogy offers does not provide the type of metalanguage and language awareness necessary to substantially “improve” writing. We could go on for several more decades problematizing the notion of “good writing,” but we should really do our students a favor and acknowledge that certain writing is valued over others, so we can start getting students to a higher level of success.

In terms of providing feedback, I believe we need to provide more visible scaffolding to help students move from a rough draft to a successful finished product. The teaching-learning cycle and explicit metalanguage is very helpful here. Teachers or specialists in the writing center need the appropriate metalanguage and genre awareness to be able to deconstruct the features of a genre to students. Next, the writing center can foster a negotiation stage, where specialists provide feedback on a draft. This process should usually be enough for students to create a revised and successful draft, but weaker writers can engage in multiple stages of negotiated revision. I know writing center pedagogy argues not to focus on local concerns; however, I believe writing center pedagogy needs to recognize that language is stratified: discourse (texts), consists of lexicogrammar (words and clauses), which consists of phonology (sounds) and graphology (letters). Each of these levels of language are important in that they build upon each other. This provides a more holistic as well as specific approach to language awareness.

Besides raising language awareness, I believe Huot provides a responsive and flexible approach to responding to writing. Drawing from Phelps, Huot argues that reading response should be a dialectical process, a conversation, between teacher and writer. Huot’s framework for Moving toward a Theory of Response is a useful model of response as a dialectical process of providing room for instruction, dialog, reflection and transformation, while understanding students’ social and institutional contexts.

Posted in Uncategorized

ENGL 829 3/29 Reflection

In response to the “consensus view” of composition studies, as reflected by the various position statements, outcomes, and frameworks, I have some concern with the lack of precise language or metalanguage about writing. The C’s position statement defines what makes “sound writing,” which brings up the question of who gets to define what writing is “sound” and how they define it. I also have a concern about the definition of genre, which I think leads many to believe that writing must conform to some arbitrary set of conventions as defined by “experts.” Instead of shaping writing towards some social context, it is the social context that shapes writing and determines the sets of values and criteria and types of legitimate knowers, who we call experts. I become concerned when genre teaching advocates following the conventions of experts in general, as that approach promotes a lack of critical awareness. Students do need to learn genre conventions but it is in the hopes that they can then become legitimate participants in the field in hopes of eventually transforming the field for the better.

In terms of transfer, I am concerned with courses that state they are specifically teaching for transfer because their methods may actually be inhibiting it. Although I think teaching rhetorical and reflective modes of awareness is certainly beneficial, I am not convinced rhetorical awareness promotes the type of high road transfer the field is striving for. I like to relate Bernstein’s notion of horizontal and vertical discourse to low road and high road transfer, respectively. Horizontal knowledge, such as learning to tie your shoes or ride a bike, is segmented within its specific, local context. The ability or skill required to tie your shoes or ride a bike is not transferred to other contexts, for instance learning to play an instrument. Vertical knowledge, on the other hand, such as in the sciences, is cumulatively built and operates at a high level of abstraction. The field of science continually moves forward by the creation of knowledge with greater explanatory power. So courses that focus exclusively on process, and not higher order critical analytic skills or in-depth knowledge content, may be segmenting learning within specific contexts. For instance, a course on the discourse of TED Talks, where students analyze the rhetoric of TED talks, remix a TED Talk, and finally create a TED Talk of their own, may teach students a lot about TED Talks, as well as some rhetorical theory and knowledge of software, but these skills may or may not be transferable in terms of high road transfer.

Finally, I have some concerns with the portfolio focus of the third wave of assessment, as Yancey calls it. I think first we need to consider what we want assessment to do. Is assessment about giving a student a grade, or is it about helping make students’ writing better? If assessment is meant to help guide students’ writing to make it better than the assessment of work must be ongoing with explicit criteria. Not to say all portfolio grading works this way, but waiting till the end of the semester to provide holistic feedback probably will not improve students’ writing. I would also be wary of handing evaluation completely over to students as a type of reflection. In general, we need to accept that symbolic capital is unevenly distributed within our society, and that some forms of writing hold more social power than others. By not providing ongoing and appropriate feedback, we are doing students a disservice by impeding their control over discourses of power.

Posted in Uncategorized

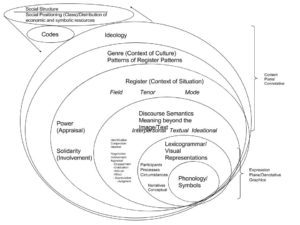

ENGL 806 Create a Sign Activity/ Stratified Model of Language

For this activity I tried to create a stratified model of language that maps the dialectical relation between social structures and the instantiation of texts. The stratified model of language was borrowed from SFL textual analysis and then adapted, following the work of O’Halloran and Kress, to images. The model maps the minutest elements of language, showing how each level of language is nested within or realizes the other. So, at the minutest level we have graphology/phonology or symbols/graphics, which are then formed into sentences or visual representations, which form a text’s meaning as a whole, which is influenced by the context of the situation (register), realized through the context of a culture (genre), influenced by ideologies, which are in turn shaped by one’s social positioning, determined by the codes generated by the social structure. As you can see, social structure ultimately generates the codes that shape texts instantiated in our culture, but texts, themselves, can go on to influence ideologies and in turn transform cultural codes and ultimately social structures. The connotative levels of meaning are parasitic, meaning they must use lower-level systems to instantiate their meaning.

I paid particular attention to mapping tenor, or interpersonal meanings here, which at the level of register forms the concepts of power and solidarity, which is instantiated as appraisal and involvement at the discourse level. Little work has been done in multimodal discourse analysis on the interpersonal aspects of visual rhetoric and ideology. I plan to further analyze how power and solidarity are conveyed within social activist memes. The model makes clear that ideological and political stances we instantiate through texts are in large part determined by our positioning within the class-based social structure.

ENGL 806 Bib #3 “Memetics—A growth industry in US military operations”

Prosser, M. B. (2006). Memetics–A growth industry in US military operations (Unpublished master’s thesis). Thesis (Master’). doi:http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a507172.pdf

This thesis argues that contemporary warfare will need to involve non-linear warfare tactics, such as the creation and distribution of memes, to influence and combat the alternative ideologies of insurgent groups operating within the 21st century, networked media landscape. Following Richard Dawkins, the author defines memes as “‘units of cultural transmission, or a unit of imitation’. Said another way, memes are bits of cultural information transmitted and replicated throughout populations and/or societies” (p. 1). The author argues the military will need to move past traditional models of combat—physical military incursions on the battlefield—and into the realm of meme warfare, if the military wants to succeed in curbing insurgent ideologies. The author argues that ideologies are inherently complex, transcendent ideas that are “difficult to eradicate kinetically” (p. 1). The author suggests that ideologies should be conceptualized from an epidemiological perspective, as a disease that “replicates and spreads” as an adaptive system. Memes, too, function as viral, replicable, adaptive systems that can counteract and persuade enemies’ beliefs in “the hotly contested battlefields inside the mind” (p. 3).

The author provides a case study of how the corporation 3M used an innovation meme to cultivate a culture of innovation within the company, which led to significant gains and financial growth. Although not directly related to military warfare, the author suggests that 3M’s corporate model, where the CEO and leaders of the company promote a meme as a “transcendent idea” that then filters down and influences employees and customers, serves as a useful model as to how meme creation can go on to “infect” stakeholders. The author suggests the development of a meme warfare center that would provide “the most relevant meme combat options within the ideological and nonlinear battle space” (p. 11). The meme center would be divided into internal and external branches. The internal meme center would be focused on generating a desired ideological climate within the military, while the external meme center would be more outward looking, promoting the cultural engineering of societies. Key to this project would be “meme engineering,” which entails “meme generation, targeting, and inoculations” (p. 14). Meme engineering is a complex and sophisticated operation, which the author believes would take an interdisciplinary team of experts in cultural anthropology, linguistics, behavioral science, game theory, cognitive scientists, and experts in warfare. Meme engineering is an iterative process that must include the continual cultural analysis of memes over time, as well as an understanding of how memes can be effectively transmitted and distributed through global media.

Although this thesis was written before the explosion of memes as we know them today, this paper still offers an eye-opening perspective on mimetic power and how memes can be used to shape and reshape ideologies. The author provides complex conceptual models of how ideologies and memes function as adaptive pathological systems. One aspect of global communication and memetic power that has certainly changed is the concept of contact. The author argues, “in the absence of contact, memes are not transmitted, replicated, or re-transmitted” (p. 4). This was obviously an issue back in 2006 when not everyone was globally connected through the internet. Now, even insurgent populations most likely have access to the internet, making contact no longer an issue: through contact, almost any ideology can be spread or combatted through social media. Also, through metadata the tracking of the propagation of memes is much easier. What I am not sure the military foresaw at this time was the bidirectional nature of mimetic warfare, where “insurgent” groups can just as easily spread and combat ideologies online.

The conceptual framework of ideologies and memes offered here will be useful to my research. I am also interested in exploring the concept of logogenesis—the evolution of signs and symbols over time— as it applies to the distribution and redistribution of memes. I find it useful that memes and ideologies are being conceptualized here within multidimensional and nonlinear space. Finally, the author provides a model of how ideologies influence behavior that I would argue is similar to Basil Bernstein’s model: “Memes influence ideas, ideas influence and form beliefs,” beliefs influence political positions, which in turn influence actions (p. 2).

ENGL 806 Timeline

For this timeline I decided to focus on the hardware and software that has been most influential in my life. My earliest memories of computing were back in computer class as a kid using an Apple II. What I remember most about using the Apple II was playing Oregon Trail and a typing game where if you spelled a word incorrectly a fly would splat onto the car windshield. The Macintosh Classic was much more user-friendly and design-oriented. This computer had an understandable desktop interface and user-friendly tools for actually creating images and products like greeting cards and brochures. Concurrently, I was even more excited about different gaming systems, such as Nintendo, Genesis, and Playstation. Although I debated whether I should include gaming systems in a timeline related to design, I cannot overlook the interactive interfaces of gaming consoles as well as the potential for user design. For instance, in the NES game Excitebike, users were able to design their own levels. There was also a capacity for hacking, such as using cheat codes, for instance the infamous code for thirty lives in Contra— up, up, down, down, left, right, left, right, B, A, start.

When I started getting into recording music, a whole new set of design tools became accessible to me. The ADAT machine was capable of recording eight tracks of digital audio on a format that looked much like a VHS cassette. Doing this activity made me reminisce on all the various formats I was using to record data. For instance, my Alesis sampler could only hold sixteen seconds of audio on floppy disks. The Roland SP 808 sampler was a great advance, recording up to twenty-five minutes of audio on a zip disk. This sampler came with a screen to actually view data, and had some amazing functionality, being able to match sample tempos.

I then got into designing sound with software. The Pro Tools system I began using had almost unlimited potential in terms of audio-visual creation. Logic Pro has even more capabilities of integrating software instruments (VSTs) with audio. Max/MSP is a programming environment, where the user can actually build multimedia software. I recorded an album with Max/Msp created solely with software I built in Max and manipulated samples.

Some of my favorite design environments are open source software, some of it even intended for children. TuxPaint is a painting program intended for kids, but the environment is really fun and it actually produces interesting images. Sound Club is an open source audio sequencer for PC that I used for a number of years. It is extremely simple to use and comes with a cheesy set of sounds, from brass, to drums, and sound effects. Sound Club makes music that sounds like old video games, a sound I particularly like, growing up with the sound design of eight and sixteen bit gaming consoles.

Posted in Uncategorized

ENGL 806 Bib 2: Stuart Hall “Encoding, Decoding”

Hall, S. (1993). Encoding, Decoding. In S. During (Ed.), The Cultural Studies Reader (pp. 90-102). London and New York, NY: Routledge.

In “Encoding, Decoding” Stuart Hall lays the groundwork for a contextualized theory of communication. Hall (1993) argues that for too long communication has been conceptualized as “a circulation circuit or loop. This model has been criticized for its linearity—sender/message/receiver” (p. 91). In response to this reductive model of communication, Hall offers a semiotic paradigm consisting of several determinate, yet interconnected, moments: “production, circulation, distribution/consumption, reproduction” (p. 91). This semiotic paradigm models the complex social relations involved in the production, circulation, consumption, and reproduction of televised discourse while accounting for misunderstandings that can arise from asymmetrical power relations between television producers and viewers. From the determinate moment of production, the power and social relations of professionals yield a code that is encoded in the discursive message of a televised broadcast. This message is eventually decoded by viewers, becoming embedded in social relations and, in turn, feeding back into the moment of production. Some codes appear to be so universal they are naturalized, taken for granted as common sense. This naturalization process has tremendous ramifications in terms of ideology, as the naturalization of codes “has the (ideological) effect of concealing the practices of coding which are present” (p. 95). Hall also makes the distinction between the denotative and connotative level of a message. At the analytical level, the denotative meaning is the literal “fixed” meaning of a sign, while the connotative meaning refers to the polysemic, open, or associative and, hence, ideological level of the sign. However, Hall is quick to point out that the denotative level is not immune to ideology. For new ideological meanings to become naturalized they must first be mapped onto new discourses that are “preferred,” preferred meanings having the backing of the dominant power structure. Hall outlines three possible subject positions for decoding meaning. The dominant hegemonic position interprets a message at its face value. The viewer receives the message exactly as the producers intend it. In the negotiated position, the viewer receives the dominant or preferred meaning, but partially contests it at some level, usually at its local application. Finally, in the opposition position, the viewer completely rejects the dominant message, instead interpreting the message from an alternative ideological framework, such as seeing the message as promoting the interests of a specific class.

Hall’s semiotic paradigm is still the most fully conceptualized model of mass communication. What makes the model so powerful is that it allows for the power dynamics, social relations, and discursive rules within the semiotic chain—from production to distribution to consumption to reproduction—to be analyzed at each determinant moment. Instead of a reductive behavioral model, which posits that a discursive message, say for instance about violence, would actually promote violence, Hall’s model is capable of analyzing the underlying social dynamics and power dynamics that generate visual discourse. The semiotic paradigm is also able to account for “misreadings” between production and consumption, as well as analyze the role the media establishment plays in the naturalization of ideologies as common sense.

In terms of my research, Hall’s semiotic paradigm allows me to link visual texts to their social contexts or culture in a dialectical way. Additionally, the model helps analyze visual texts at stratified levels, including their denotative “natural” level and their connotative, ideological level, while being able to situate visual texts intertextually. From the article, it is uncertain whether Hall foresaw the rise of user-generated content or alternative media. New media brings up several questions in terms of the application of Hall’s model, including how it is applied to the subject position of viewers. Although most social media activism is coded as revolutionary, as Marx noted, “The ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas.” So, messages coded as revolutionary on social media may be, in fact, still operating from a dominant hegemonic position, whereas alternative media most likely operates strictly within an opposition code. Applied to a contemporary context, Hall’s work shows an increasing polarization between the dominant and opposition codes, with less space for a reasonable negotiated position. Although Hall may not have predicted the rise of social and alternative media, his theory still accounts for it, as user-generated content feeds back into the professional moment of production.

Posted in Uncategorized

ENGL 806 2/16-23 Visual Argument: Smokey Says, Resist

In their groundbreaking book Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, Kress and van Leeuwen (2006) write that “Just as grammars of language describe how words combine in clauses, sentences and texts, so our visual ‘grammar’ will describe the way in which depicted elements—people, places and things—combine in visual ‘statements’ of greater or lesser complexity and extension” (p. 1). Following their work using SFL, I view the clause (the configuration of participants, processes, and circumstances) as the basic unit of experience, which also applies to images in terms of the construction of visual arguments as well. Designers create visual arguments using the available semiotic resources of their social contexts. I do not believe images can be created without some linguistic or contextual reference, as by definition, visual arguments are socio-semiotic constructs.

Smokey Bear Resist T-Shirt

When discussing the three sites of visual production—the technological, compositional, and social—Rose (2012) uses the work of Marxist and critical geographer David Harvey to help elucidate, in Harvey’s terms, The Condition of Postmodernity (1989) of our contemporary social environment. Here, I will briefly apply a “Harvey-ian” lens to the above image of Smokey The Bear as an activist, created after a faction of the National Park Service recently went “rogue.” Harvey (2005) argues that neoliberalism has radically restructured the economic and social landscape, creating a ruling elite of tech CEOs and billionaires, whose hegemonic ideology frames an interventionist, neo-imperialist foreign policy as a radical form of personal liberation and social justice. Central to neoliberalism is the co-option of 1960s activist discourses and new social movements centered on civil rights and sexual and identity politics, to legitimize and normalize state and global control in the hands of a few elites. The Smokey The Bear Resist image plays into a radical chic neoliberal doctrine of pseudo-activism, by coding a message in support of maintaining the status quo (a decades-long politicized techno-environmental science agenda) as an edgy social justice issue. Harvey’s method allows for a deeper, ideological critique of internet activism that would be nearly impossible to uncover from the mere denotative level of the visual argument. The Marxist irony is not lost, as this supposedly anti-consumerist message is being sold on t-shirts for $22.99.

Why This Method For This Artifact?

The theoretical methodology I am developing is a Frankentheory that needs to be capable of analyzing visual texts as well as their dialectical relations to culture. This notion of modeling both a text and its social relations comes from SFL, especially Firth, Hasan, and Halliday’s argument that language can only be understood within its context of cultural-use. Hasan (2016) writes, “the relation between language and society is dialectical. Language creates, maintains, and changes human society while this stable and yet forever changing society puts pressure on linguistic resources for making a specific range of meanings, with consequences that are far-reaching indeed for both language and society” (p. 12).

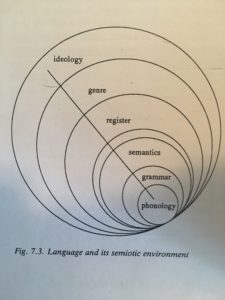

To analyze memes as visual texts I will be using SFL, specifically the stratified view of language pictured below. This model views language from the ground up at various stratified levels, beginning with the minutest level of phonology, to lexicogrammar, to discourse semantics (the text as a whole), to register (the context of situation dealing with field, tenor, and mode variables), to the context of culture (genre, a pattern of register patterns), to ideology. The level of ideology has been added to take into account patterns of meaning that cannot be understood by the text, register, or genre, alone. I will be applying this method of textual analysis to memes. Here the expression plane of phonology and grammar is represented by visual signifiers, while the content plane that goes beyond the text—register, genre, and ideology— will be considered the signified. Register analysis will be essential for understanding visual narratives in terms of the field (the experiential level of participants, processes, and circumstances), tenor (the emotional level, attitude, solidarity, power), and mode (the channel(s) of communication). Following Poynton (1992), ideology will be considered as dealing with evaluation (some form of judgment) and in terms of binary oppositions— “male/female, capitalism/socialism, war/peace,” etc. (p.10).

Yet, just analyzing visual texts with this stratified model of language is not enough to gain a full understanding of the dialectical relations between visual texts and culture, so from the cultural perspective I will be drawing from the work of cultural theorists such as Stuart Hall, Raymond Williams, Basil Bernstein, and Jean Baudrillard. This methodology should provide a more fully contextualized and dialectical framework for understanding the role ideology plays in the construal of visual texts in our culture.

The method used to analyze this particular artifact draws from the cultural studies side of my framework by operationalizing several of Harvey’s concepts in terms of Neoliberalism and pseudo-activism to better understand the connotative meaning, motivations, and power relations, behind social media activism.

Language and its semiotic environment (Martin, 1992, p. 496)

What Did The Analysis Reveal?

The analysis reveals a deeper ideological level embedded in the text that is difficult to retrieve solely from the denotative level. At the denotative level, the image conveys an unproblematic liberal humanist message about standing up for one’s beliefs and the environment against those willing to destroy it. At a deeper level, however, the analysis reveals a complex ideological system with possibly unstated ulterior motives. These ulterior motives can manifest as “weaponized discourse,” think the “meme wars,” unduly influencing viewers with sophisticated ideologies at an almost subconscious level. Within this framework, social structures generate specific codes based on class-specialization, giving rising to various forms of consciousness. In general, members of the old middle class believe in a strong classification (such as border walls, extreme vetting), while the new middle class believes in weak classification (open borders, weak categorizations of gender roles, etc.). These sorts of class-strata differences in terms of code, realized through visual texts such as memes, lead to ideological conflicts within the the middle class, potentially causing economic, social, and ideological divisions.

What Does The Analysis Miss?

At this point in time, this analysis misses the “how” of visual texts. From a semiotic perspective, how does the image of Smokey the Bear convey its specific denotative and ideological messages? This is where visual analysis using SFL comes into play, especially a register analysis of field, tenor, and mode. But as stated earlier, mapping the ideological plane is necessary for a full understanding of the text, so that is why a dialectical theory of text and culture is necessary.

References

Harvey, D. D. (2006). A brief history of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA.

Hasan, R. (2016). Context in the system and process of language (J. Webster, Ed.). Sheffield, UK: Equinox.

Kress, G. R., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). London: Taylor & Francis.

Poynton, C. (1992). Language and gender: making the difference. Geelong, Australia: Deakin University Press.

Rose, G. (2011). Visual methodologies: An introduction to the interpretation of visual materials (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

J.R. Martin, “Grammaticalising Ecology: The Politics of Baby Seals and Kangaroos” Bib Entry 1

Martin, J. R. (1986). Grammaticalising ecology: The politics of baby seals and kangaroos. In T. Threadgold, E. A. Grosz, G. Kress, & M. A. Halliday (Eds.), Language, Semiotics, Ideology. (Vol. 3). Sydney: Sydney Association for Studies in Society and Culture.

In “Grammaticalising Ecology,” Martin argues a fourth level of ideology needs to be added to SFL’s three-tiered, multi-stratal model of language. Unlike denotative semiotic systems such as music, where there is a one-to-one correspondence between meaning and expression, Martin (1986) believes connotative semiotic systems are parasitic—”they don’t have a phonology of their own; instead they take over another semiotic system as their expression form” (p. 226). In this model, language serves as the expression of register (the context of situation made up of field, tenor, and mode variables); register serves as the expression of genre (the context of culture made up of register patterns); and genre serves as the expression of ideology (p. 226). However, these patterns of meaning can cut across various levels, as ideology can be encoded in lexis (wording), for instance, calling a crowd a mob or riot. Martin argues that without theorizing a plane of ideology it is difficult to predict why certain groups choose different genres for communication, and it is also difficult to predict how genres will be realized in specific contexts. A looming question regarding ideology is the role of access in terms of what social groups have access to what meanings.

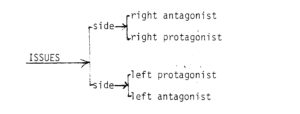

In the article Martin provides a model for mapping the ideological positions of different social groups in terms of their stances towards political issues. Martin (1984) believes it is useful to look at disputes as “ideology in crisis”: “When ideology is in crisis, the linguistic choices reflecting one or another stance are foregrounded” (p. 228). Martin’s model for ideology in crisis begins with a particular issue. Issues have two sides, pro and con. On each side there are antagonists, those concerned with stirring up an issue, and protagonists, those concerned with resolving disputes in an effort to maintain the power of the dominant group. The full model divides issues into Right and Left sides, the Right concerned with maintaining power and the Left concerned with gaining power, each side also containing antagonist and protagonist roles (see Figure 1.).

Figure 1. Issues as ideological systems

Martin uses this model of ideological systems to analyze two texts. The first text, from Habitat: A Magazine of Conservation and Environment, discusses whether Australia should kill kangaroos for population control, while the second text, taken from International Wildlife: Dedicated to the Wise Use of Earth’s Resource’s, discusses whether Canada should continue to hunt baby seals. As a magazine dedicated to environmental activism, Habitat could be said to be on the political Left, while International Wildlife, dedicated to more “conservative” forms of conservation, is on the Right. Both texts use different genres to achieve their social purpose. Text 1 is an example of a hortatory genre to provoke a call to action. In terms of register, text 1 uses more dramatic lexis, using words like killing and murdering to convey the injustice of slaughtering kangaroos. Text 2, on the other hand, is expository and analytical, concerned with preserving power. Text 2 is less emotional, using words like population control and wildlife management, positing seals as a natural resource to be controlled responsibly.

While the modeling of ideological systems is still in its early stages, Martin does raise several questions related to meaning, texts, and ideology. What ideologies and range of meanings do different social groups draw from? How can social groups “stir up” and resolve ideological conflicts through discourse? How do social groups mischaracterize and attack their opposition intertextually?

I will be able to draw from Martin’s work by applying this linguistic model to the realm of images. This model will be useful in analyzing the “meme wars” of our current political climate. Martin’s approach provides a tangible method for beginning to understand the complex relations visual rhetoric has to design, text, intertextuality, power, and social context. By mapping an ideological plane of visual rhetoric, rhetoricians have more systematic tools for understanding the gendering of discourses, as well as the unequal distribution of access to genres in terms of social power.