Introduction

At the moment I do not see multimodal composition having an agreed upon object of study. As Claire Lauer points out, we need “precise definitions” in multimodal composition, but we also need precise objects of study (39). The lack of precision in terminology and objects of study has to do with the fact there is no metalanguage to discuss and analyze multimodal texts in rhet/comp.

While a rhetorical approach to multimodal texts is essential to understanding new media, rhetorical analysis can only attend to new media objects (Manovich’s term) on a holistic level, the broad analysis of a text’s purpose, audience, genre, and context (14). A rhetorical analysis cannot, for instance, explain intersemiotic complementarity, how the multiple modes of a new media object combine to create new, multiplicative meanings. For this type of in-depth analysis, a functional, social semiotic metalanguage is necessary.

Secondly, the objects of study in multimodal composition have been imprecise because the focus has not been on analyzing new media objects, it has been on producing them. Using technology is not really an object of study. Additionally, the emphasis on technology leads to confusion over how to assess students’ multimodal projects.

I propose the objects of study in multimodal composition are twofold: new media objects and student writing. Student writing could be defined as traditional or new media texts, though I am focusing solely on traditional writing. To analyze these objects of study, I draw from multimodal social semiotics and genre pedagogy.

Object of Study #1: Analyzing New Media Objects

When incorporating new media in the classroom, students first have to be able to analyze new media. Multimodal social semiotics is a thriving field which utilizes systemic functional linguistics and a social semiotic framework to describe and analyze new media. By drawing on multimodal social semiotics, teachers can provide students with a framework and toolkit for analyzing new media, while also introducing a functional metalanguage that positively benefits students’ literacy and increases students’ powers of noticing (de Oliverira and Schleppegrell 16).

The most popular new media objects to be analyzed in the classroom are websites, images, and videos. In the FYC course I teach, the major unit focuses on consumerism and advertising, in which students research the advertising strategies of a brand or celebrity and write an annotated bibliography, literature review, and argumentative paper on a controversial aspect of a brand’s marketing. This unit allows for the in-depth analysis of all kinds of new media objects, including websites, print ads, commercials, and social media.

Websites are a rich source of analysis, especially with branding, because websites are the face that a person or corporation wants to present to the world. Hence, websites are the lens from which corporations or individuals present their ideology. There has been a fair amount of research on visually analyzing websites by Jay Lemke, Gunther Kress, Theo van Leeuwen, and others. In “Travels in Hypermodality,” Jay Lemke provides a visual analysis of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center website. Lemke uses Halliday’s metafunctions (ideational, interpersonal, and textual) to guide his analysis, but Lemke recasts the metafunctions as presentational, orientational, and organizational meaning (3). Visual analyses of websites are usually incredibly descriptive and detailed. Lemke goes into a massive amount of detail, annotating and analyzing the content of the website – hyperlinks, images, navigational features.

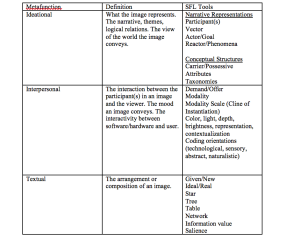

Kress and van Leeuwen provide a semiotic framework in Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, which works well for describing websites, images, and video. Each metafunction contains tools that can be applied in a semiotic analysis. Along with the Aristotelian appeals (Ethos, Pathos, Logos), students can apply the semiotic toolkit for a deeper analysis of new media objects (see fig. 1). For instance, with the ideational metafunction, students label participants as actor and goal, look at logical and taxonomic relationships, and see how vectors create action in visual narratives. With the interpersonal metafunction, students label whether participants are using a demand gaze or offer, distinguish the modality of the image-text (how truthful the image seems), and look at the coding orientation (what group the text was made for – scientists, consumers, artists, etc.). The textual metafunction views the arrangement of a screen-text, and the tools here relate to information value – given/new, ideal/real – as well as typographic features.

Object of Study #2: Student Writing

The second object of study pertains to how students write about new media. I believe this skill is crucial, even more so than producing new media, especially in the composition classroom. Here I am referring to traditional writing as the object of study, specifically, how students take the theoretical framework and metalanguage outlined above and recontextualize it into their writing practices.

This new object of study is informed by genre pedagogy and discourse analysis. In a previous post, I outlined the Onion of Critical Analysis, which could be productively applied to an analysis of students’ writing on new media. The Onion consists of four levels working in a spiral, each level supporting the next – description, analysis, persuasion, and critique (Humphrey and Economou 41). At the most fundamental level, students must describe websites, images, and videos. This mostly takes the form of narrative description, summarizing an image-text, as one would summarize a scholarly article. Next, students analyze new media, using the Aristotelian appeals and the semiotic toolkit. Third, students analyze the persuasive features of texts, as well as use these texts in their argument to persuade the reader. Finally, the most sophisticated skill, students critique new media, building upon the other analytical skills.

What I have found most interesting while researching this object of study is the creative, generative ways in which students apply the metalanguage to an analysis of their new media sources. Students use the toolkit in ways I would never have thought to apply them because I am used to using these terms only in the ways discussed by Kress, Lemke, and others. Without this theoretical grounding, students are much more likely to apply the metalanguage in unique ways, making insightful, new connections. The metalanguage also helps students become detail oriented, as they scrupulously analyze the ideational, interpersonal, and textual meanings of new media.

Conclusion

By defining the objects of study of multimodal composition to be twofold – new media objects (websites, videos, images, etc.) and student writing – we can come to a precise definition of the field. The two objects of study tie directly into the two major questions: the “what” and “how” of multimodal pedagogy.

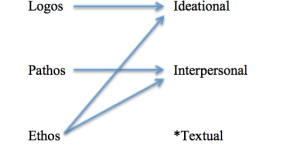

A purely rhetorical approach does not go into the depth necessary to analyze new media, so a metalanguage of new media is essential. Interestingly enough, systemic functional linguistics, the most utilized metalanguage for new media, is a rhetorical grammar, much more rhetorical than the prescriptive, rules-driven grammar so often used in composition, as Halliday makes clear in “Ideas About Language” (22). By adding just a few more terms to our rhetorical lexicon, such as modality, given/new, ideal/real, and organizing our analyses from the tri-focal perspective of the metafunctions (ideational, interpersonal, textual), which directly relate to logos, pathos, and ethos, we arrive at a precise, in-depth rhetorical metalanguage for new media (see fig. 2).

Researchers have been using a social semiotic metalanguage for over two decades, but it has yet to be well-known or utilized within rhet/comp, which is still mainly technology-driven and product-focused. It is essential we give students a way of critically analyzing new media, so, as Douglas Rushkoff says, students become the programmers, not the programmed (“Program or be Programmed: Ten Commands for the Digital Age”).

Works Cited

De Oliveira Luciana, and Mary Schleppegrell. Focus on Grammar and Meaning. Oxford.: Oxford UP, 2015. Print.

Humphrey, Sally L., and Dorothy Economou. “Peeling the Onion – A Textual Model of Critical Analysis.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 17 (2015): 37-50. Web.

Lauer, Claire. “Contending with Terms: ‘Multmodal’ and ‘Multimedia’ in the Academic and Public Spheres.” Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook. Ed. Claire Lutkewitte. Boston: Beford/St. Martin’s, 2014. 22-41. Print.

Lemke, J. L. “Travels in Hypermodality.” Visual Communication 1.3 (2002): 299-325. Web.

Kress, Gunther R., and Theo Van Leeuwen. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. London: Routledge, 1996. Print.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2002. Print.

2 responses to “Paper # 3 Objects of Study OoS”