Introduction

Throughout the semester, I have revised and refined what it means to be a scholar of systemic functional linguistics (SFL). One aspect of my thinking which has been solidified, when putting my viewpoint as a scholar in conversation with other debates and camps in English Studies, is that I consider myself a scholar of rhetoric and composition using SFL as an applied linguistics to solve certain issues of theory and pedagogy. This semester I have focused on two major areas: multimodal composition and literacy pedagogy. In both areas, I have used SFL to supplement traditional approaches to these fields. For me, SFL helps alleviate several cognitive dissonances that have arisen in my research and teaching practices, and possibly within education in general. A functional approach to language requires completely different habits of mind than a traditional teacher/scholar. Acquiring these new habits of mind has not come without some difficulties. Addressing cognitive dissonances has made me think in new, unexpected ways, see my students and their writing in a different light, and even helped my students to begin to see language functionally as well. Learning, or relearning, to see language functionally, which Halliday argues is the way children see language before going to school, seems to make more sense for me as a teacher and for my students (21). A functional approach requires a good deal of theoretical and professional knowledge, working as a generalist in the intersection of a variety of fields – rhet/comp, linguistics, genre pedagogy, semiotics, multimodality, digital rhetoric, English for Academic and Specific Purposes, and English as a Second Language. Currently, I see my contribution to English Studies being helping to develop a metalanguage in first-year and advanced composition that students can use to discuss and analyze texts, print and digital, which also serves to strengthen literacy of all students. To accomplish this, I have been researching SFL as a metalanguage to integrate multimodal discourse analysis (MDA), genre pedagogy, and critical language awareness into the composition classroom.

New Media and Multiliteracies

As educators, I feel we need to constantly reassess the changing world our students and we are living in, especially in terms of literacy and lifeworlds. To better understand the sociocultural impact of new technologies and globalization, I often draw on the work of media theorist Marshal McLuhan and the works of Gunther Kress, Norman Fairclough, David Harvey, and the New London Group (NLG). Two essays, the NLG’s “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures” and Kress’s “Gains and Losses: New Forms of Texts, Knowledge, and Learning,” have been particularly useful in helping frame these societal shifts and what it means for literacy pedagogy. Kress discusses this technological shift as a revolution in modes, forms of communications, and mediums, the technological ways of disseminating information, with its concomitant rise of “pessimism … and unwarranted optimism” within education (6). Yet, this shift does not solely have to do with technology but the diversification of local and global cultures as well. The NLG uses the term “multiliteracies” to describe this twofold revolution, a revolution in new media as well as language diversity and lifeworlds. Although I find the term “multiliteracies” vague and problematic, a careful definition of the word does cover what I am trying to do as a scholar, and I think it summarizes the work of the NLG I follow.

The definition of multiliteracies encompasses new media and literacy pedagogy, new media in that digital media has arguably surpassed print as the dominant medium of communication and literacy pedagogy in that educators must teach literacy to a whole new demographic of learners. Although I have not adopted all aspects of the NLG’s work, I do sincerely believe we in comp/rhet need a functional grammar and that composition benefits from being situated within the sociosemiotic realm of design. The NLG writes, “In other words, they [teachers and students] need a metalanguage – a language for talking about language, images, texts, and meaning-making interactions” (77). As a functional metalanguage and grammar, SFL has proven to be the most flexible metalanguage for a multiliteracies project. First, SFL is unlike traditional grammar in that it looks at language as a resource, not a set of prescriptive rules. In a functional approach to grammar, nouns are called participants, verbs are processes, and prepositional and adverbial phrases are circumstances. Functional grammar can work much better for English Language Learners and non-traditional students. Secondly, Kress, van Leeuwen, and others have already adapted the SFL metalanguage to new media. I find current approaches to new media lacking in that most scholars ignore multimodality’s origin in SFL, social semiotics, and design and focus almost exclusively on student production, which does not address the larger issue: the interpretation and analysis of new media, a crucial skill to have in the digital age. My original contribution is tying multimodal analysis to literacy pedagogy. Students can first learn SFL through analyzing new media and then apply what they have learned to an analysis of traditional texts, reinforcing literacy skills in the process.

Genre Pedagogy

Next I want to focus on what it means to be a genre pedagogy scholar and how this differs from the dominant form of instruction in rhet/comp – process pedagogy. As a disclaimer, I find nothing particularly wrong with process pedagogy. I am not looking to replace rhetorical theory or process pedagogy, only supplement them. It is true that rhetoric is already a metalanguage, but not in the grammatical sense. Rhet/comp still uses formal grammar almost exclusively. I think a lot of the backlash against language in English education, especially the reaction against Current Traditionalism, is in fact a reaction against formal grammar, the dictation of “right” and “wrong” ways of writing and speaking, going so far as to view people who do not write “properly” as somehow deficient. In “Ideas About Language,” Halliday argues functional grammar is the language of rhetoric, tracing functional approaches to language all the way back to Ancient Greece and the Sophists (23). Instead of focusing on grammar as a set of rules, functional grammar analyzes how language makes rhetorical meaning within social context. If rhet/comp adopted a functional grammar, there might be less cognitive dissonance in certain areas of praxis and theory.

My issues with process pedagogy are minor, but they do have significant consequences for composition research as well as the way we view students. Halliday, Ken Hyland, J.R. Martin, and Mary Schleppegrell have all helped me see literacy pedagogy in a new light. Besides the insights into process approaches Halliday offers in Language as Social Semiotic. Hyland’s essay “Genre-Based Pedagogies: A Social Response to Process” has been incredibly influential to my work. Hyland writes, “process represents writing as a decontexualized skill by foregrounding the writer as an isolated individual struggling to express personal meanings. Process approaches are what Bizzell (1992) calls ‘inner-directed'” (18). Theorizing writing as an “inner-directed” process is problematic for several reasons. First, there is no way to systematically study language in the shadowy realm of the mind. Rhet/comp studies writing using a cognitivist approach, such as think aloud protocols, which has always struck me as a bit odd. Think aloud protocols do have their merit; however, under this assumption, one would have to be a cognitive scientist, a sub-field of psychology, just to study language and meaning. Instead of analyzing what professional writers have to say about their writing process, why don’t we just study their writing in social context? Secondly, as Hyland and other genre pedagogists point out, process pedagogy’s inner-directed approach of self-discovery is a relic of a bourgeois era in which predominantly white, middle class students came to school already proficient in English and understanding of the implicit demands of their teachers. Amy Delpit argues focusing on process over product “do[es] students no service to suggest, even implicitly, that ‘product’ is not important. In this country students will be judged on their product regardless of the process they utilized to achieve it” (qtd. in Hyland 19). I have seen a focus on process with most teachers, but especially teachers of cultural studies and social justice. Although incredibly well-meaning, and certainly raising students’ awareness of political and sociocultural issues is important, the one thing most teachers do not teach is how to actually write. There is so much confusion over literacy pedagogy, that many argue it is impossible to teach writing, or there is no such thing as “good” or “bad” writing. Indeed, many educators argue students have a right to their own language and should, therefore, not be instructed in academic genres. In genre pedagogy, teaching students to become successful writers is a matter of social justice. Students will continually be assessed throughout their education by their writing, and advanced writing and communication skills are essential to enter professional discourse communities, the only pathway for ELLs and traditionally marginalized students to raise their socioeconomic status.

So how does a teacher go about teaching a literacy pedagogy that addresses the needs of all students, yet which is not formulaic, encouraging rote instruction and conformity? Genre pedagogy was developed by students of Halliday to meet the increasing literacy and population demands in Australia. Australia had adopted process pedagogy from the U.S., but politicians, parents, and educators soon realized an implicit approach to language instruction was not addressing the literacy challenges of Australia’s diverse group of immigrants and Aboriginal population. Halliday and his students very much saw genre pedagogy as a matter of social justice, as marginalized populations were not taught the literacy skills necessary for even menial jobs.

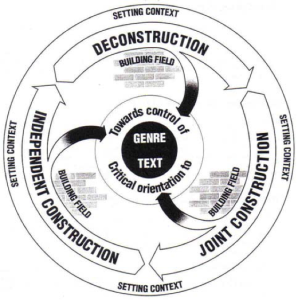

Figure 1 Genre Pedagogy Cycle

In “Designing Literacy Pedagogy: Scaffolding Democracy in the Classroom,” Martin and Rose outline a genre-based approach to literacy, an approach that seeks to meet the demands of every student. A major component of genre pedagogy is the teaching/learning cycle. Most teachers know the teaching/learning cycle as modeling – I do, We do, You do. Genre pedagogy develops modeling further. In genre pedagogy, these stages are called Deconstruction, Joint Construction, and Independent Construction (see figure 1) (Martin and Rose 2). Setting the context and building field (topic/genre/social setting) are essential at each stage. In the deconstruction stage, the teacher deconstructs a given genre, for example, the academic essay. In relation to my teaching, I would deconstruct an academic essay by reading the essay with the students and then break the essay down into its stages and even further to the phases of each stage. At each stage I provide explicit instruction in the types of writing and linguistic resources students can draw on given the genre, or field. In the Joint Construction stage students construct a text together in the style and genre of the model. Martin and Rose use a Detailed Reading Interaction Cycle – Prepare, Identify, and Elaborate – for the Joint Construction stage, as a way of engaging with students, eliciting questions and response. Although the Detailed Reading Interaction Cycle might be meant specifically for younger students, I still think it provides a useful model for teacher-student interaction, which works as a form of knowledge, consensus, and field building as well as scaffolding. Also, Joint Construction might not work well with college students. I like to think of group work as Joint Construction. I have never enjoyed assigning group work just to kill time, so I like to think of group work as a Joint Construction stage in which students can work together to understand and engage with new ideas and concepts. Finally, Independent Construction is when students write a paper independently. For major papers I like to provide students comments on a rough draft as well as have students do a peer review. This is where I think the benefits of process pedagogy come into play – the prewriting, writing, peer review, revision process composition teachers know so well. I believe teacher and peer comments not only provide useful feedback, they also provide extra scaffolding that is especially helpful for ELLs and non-traditional students.

A functional approach to language allows teachers to view students and their work in a more positive and accepting light. Instead of looking at students as rule breakers and language deficient, teachers using a functional approach see students as meaning makers. Students’ work is not judged primarily for how well they follow grammatical rules, though genre teachers are always pushing their students to produce the most successful writing they can, but educators are also concerned with what students have to say and how they are saying it. Another aspect of genre that has helped me reach out to my most challenging students is continually reapplying scaffolding and feedback. Challenging students will not reach the desired target the first, second, or even third attempt. Instead of writing these students off, it is essential to keep an open dialog with them, provide extra scaffolding and feedback, and let them try to reach the target goal again. In genre pedagogy, the desired result is not for a few students to be evaluated as successful, but all members of the class to be evaluated as successful by the end of the term.

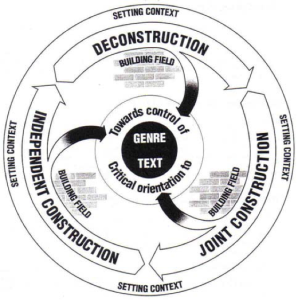

Figure 2 Bernstein’s Four Types of Pedagogy

I will briefly mention Bernstein’s Types of Pedagogy and the pedagogy I most identify with. Bernstein imagines pedagogy operating on a vertical axis (change from Intra-Individual to Inter-group) and the horizontal axis, a pedagogy based on acquisition and competence to a pedagogy based on transmission and performance, to create four distinct types of pedagogy (see figure 2). Additionally, the left side of this chart deals with invisible pedagogies and the right side visible pedagogies. In this model, all process approaches would be considered invisible pedagogies, as language instruction is not taught explicitly and knowledge is not hierarchical. Personally, I identify with the pedagogy on the right side of this model, visible pedagogy, specifically subversive pedagogy. Subversive pedagogy, unlike what the name might suggest, is concerned with effecting change through explicit instruction of inter-dynamic groups. I believe this is really the only kind of instruction that can effectively address the literacy needs of a all learners.

Conclusion

I have the wonderful opportunity of working in an English department that allows me to try new methods of instruction, integrating SFL, visual analysis, and genre pedagogy into the curriculum. From an administrative perspective, a functional approach to literacy pedagogy can seem like a win-win. First, a functional approach is inexpensive, the only expense being curriculum development if other teachers are going to learn this method. Secondly, a functional approach addresses the literacy needs of all students. ELLs and non-traditional students do particularly well with this method. From a student perspective, my students often tell me that learning multimodal visual analysis is their favorite part of the course and that they have been able to use multimodal analysis in other courses and their daily lives. Students also tell me they feel more confident writing papers. I especially am happy with the progress of ELLs and non-traditional students, as they always leave the course more confident and better writers. A functional perspective allows me to have a slightly different kind of relationship with my students. Many, usually, nontraditional students, say they appreciate the different way I teach and they respond more to this approach. Indeed, like many of my “non-traditional” students, I have developed this approach to language from many years as a frustrated student myself. I hope to continue researching, writing about, and practicing a functional approach to language in the composition classroom, helping students analyze texts of all types while strengthening literacy and critical awareness.

Works Cited

Halliday, M.A.K. “Ideas About Language.” On Language and Linguistics. Ed. Jonathan J. Webster. London: Continuum, 2003. Print.

Kress, Gunther. “Gains and Losses: New Forms of Texts, Knowledge, and Learning.” Computers and Composition 22.1 (2005): 5-22. Web.

Martin, J. R., and David Rose. “Designing Literacy Pedagogy: Scaffolding Democracy in the Classroom.” Continuing Discourse on Language. Ed. J. Webster, C. Matthiessen, and R. Hasan. London: Continuum, n.d. 1-26. Print.

The New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review 66.1 (1996): 60-93. Web.