A History of Systemic Functional Linguistics

Michael Alexender Kirkwood Halliday

Key terms: Systemic functional linguistics, social semiotics, genre pedagogy, multimodal discourse analysis

Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) was developed in the mid-twentieth century by the linguist Michael Halliday. Associated with the Prague School, and influenced by sociologists such as Malinowski and Bernstein, SFL is an extension of the work in systemics by Halliday’s mentor, J.R. Firth. SFL is a descriptive, functional grammar that has become central to many fields of research, including social semiotics, multimodality, critical discourse analysis (CDA), genre pedagogy, and natural language processing. Halliday explains SFL’s groundbreaking view of language: “A language is a resource for making meaning, and meaning resides in systemic patterns of choice” (Halliday and Matthiessen 23). SFL maps the paradigmatic dimensions of language, language as choice, using system networks.

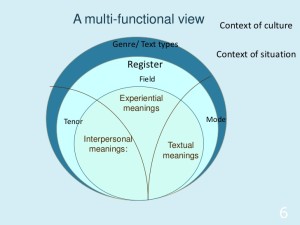

SFL’s conception of language is unique within the field of linguistics; language is viewed from multiple levels of stratification: “phonology (systems of sounds/writing), lexicogrammar (systems of wording), discourse semantics (systems of meaning), and context (genre and register)” (Zappavigna 793). In SFL, wording and grammar are not separate; instead, grammatical meaning and lexical meaning are inseparable aspects of lexicogrammar. SFL is an alternative to Chomskyan linguistics, though both systems can work hand in hand. In “On Communicative Competence,” Hymes points out the somewhat unproductive divide between competence and performance in Chomsky’s traditional linguistic framework (55). SFL bridges this divide through the concept of instantiation, where the meaning potentials of one’s language are instantiated or realized through text production. A key concept of SFL is the metafunctions. Texts convey three kinds of meaning simultaneously: the ideational (experiential and logical representations), interpersonal (social relationships), and textual (information flow and arrangement).

Halliday taught at the University of Sydney in Australia from 1976 to 1987, where he influenced a generation of linguists. His influence has been felt among English, communications, and education departments around the world. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar, published in 1985, was the first book to provide a systematic introduction to SFL, sparking interest in the field. In the following years, a host of other introductions to SFL were published, many by Halliday’s students and colleagues, including Bloor’s Functional Analysis of English, Eggins’s Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics, and Working with Functional Grammar by Matthiessen, Martin, and Painter.

Soon linguists began to expand Halliday’s work in a number of directions. In The Language of Evaluation, J.R. Martin extends the interpersonal metafunction into a full-blown theory of appraisal analysis, studying how people express emotions, make judgments, and show appreciation (35). Martin and others have also been integral to the development of genre pedagogy, which aims to teach students the explicit linguistic features of academic genres as a matter of social justice, by giving disadvantaged students and English Language Learners access to privileged forms of discourse.

Halliday’s work is extremely influential to social semiotics and multimodality. Halliday’s 1978 collection of essays Language as Social Semiotic created the field. While traditional semiotics views the connection between signifier and signified as arbitrary, social semiotics views this relationship as socially motivated. Producers use the semiotic resources available to them within the culture to create texts (books, paintings, digital artwork, etc.). As an adaptable metalanguage, SFL can map various semiotic systems – visual texts, sound, architecture, etc. O’Toole’s Language of Displayed Art was the first book to apply metafunctional analysis to the visual arts. Kress and van Leeuwen expand on O’Toole’s research in Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design, creating a framework for the analysis of screen-based texts. Multimodal Discourse Analysis (MDA) and Systemic Functional Multimodal Discourse Analysis (SFMDA) are now thriving fields of research with notable scholars including Kress, van Leeuwen, O’Halloran, and Lemke.

Arguably, SFL made its way to English Studies in the States through the New London Group’s (NLG) 1996 essay “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” The NLG is an interdisciplinary group of influential researchers, several of whom (Fairclough and Kress), are well versed in SFL. While the NLG take a lot of ideas from SFL and social semiotics, they do not outline its full theory. Although the NLG’s essay is highly influential, especially within multimodal composition, I argue that the NLG’s most important recommendation, the need of a metalanguage for teachers and students to analyze texts, print and digital, has not been fully carried out in an educational context (77).

Although SFL is the dominant form of linguistics in Australia, as well as some other pockets of the world, at this point in time I believe SFL has a very tenuous or burgeoning relationship with English Studies in the United States. Multimodality, multimodal composition, new media, and digital rhetoric have become increasingly popular in English Studies, yet these disciplines appear separate from their original contexts within SFL and social semiotics. In education, however, genre pedagogy has begun to take some hold, primarily through the work of Mary Schleppegrell at the University of Michigan.

I find this to be an extraordinarily exciting time to be working in SFL, as SFL is being applied to new fields such as social media. SFL will continue to offer functional solutions for the systematic study of language. I believe we need to do a better job in the States to communicate with SFL researchers from around the world.

Works Cited

Halliday, Michael, and Christian M.I. Matthiessen. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar. 4th ed. New York: Routledge, 2014. Print.

Hymes, Dell. “On Communicative Competence.” Sociolinguistics: Selected Readings. Eds. J.B. Pride and J. Holmes. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1972. 53-73. Web.

New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review 66.1 (1996): 60-93. Web.

Zappavigna, Michele. “Ambient Affiliation: A Linguistic Perspective on Twitter.” New Media & Society 13.5 (2011): 788-806. Web.