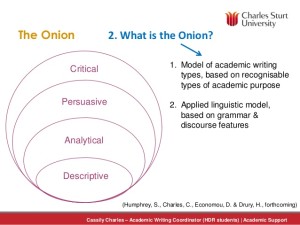

I am now turning my attention from genre pedagogy to multimodal pedagogy. My previous postings are not for naught, however. My conception of multimodal pedagogy allows for the navigation between genre pedagogy, multimodal analysis, and critical discourse analysis using systemic functional linguistics (SFL). Specifically, borrowing from my previous PAB on The Onion of Critical Analysis, I will study how students use the SFL metalanguage to describe, analyze, and critique multimodal texts. For now, I will be looking at two major questions: the “what” and “how” of multimodal pedagogy.

The “What” of Multimodal Pedagogy

The two questions – the “what” and “how” of multimodality – were first raised in the New London Group’s influential work “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures,” published in 1996. The NLG’s document was groundbreaking in the field of composition, framing all discussions on multiliteracies, multimodality, multimodal composition, new media, digital rhetoric, and any other fancy terms you want to call it, that followed.

First, we want to extend the idea and scope of literacy pedagogy to account for the context of our culturally and linguistically diverse and increasingly globalized societies, for the multifarious cultures that interrelate and the plurality of texts that circulate. Second, we argue that literacy pedagogy now must account for the burgeoning variety of text forms associated with information and multimedia technologies. (NLG 60)

To the first point, the NLG describe the shift in our society from the Fordism of production lines, ” a division of labor into minute, deskilled components,” to a Postfordism, global society with a horizontal power structure and “‘multiskilled,’ well-rounded workers who are flexible enough to be able to do complex integrated work,” where the workplace is centered around teamwork, and managerial discourses tend to infiltrate all aspects of social life, education, community, and the workplace (66). To their second point, the shift to a global, screen-based society requires educators to transform their theoretical frameworks and methods, embracing a diversity of literacies, the languages of diverse cultures, as well as the literacies and semiotic systems of new mediums, such as television, film, music, and the Internet, literacies that go beyond the “dominance” of standard print.

The Metalanguage of Design

“In addressing the question of literacy pedagogy, we propose a metalanguage of multiliteracies based on the concept of design” (73).

“In other words, [teachers and students] … need a metalanguage – a language for talking about language, images, texts, and meaning-making interactions” (77).

Gunther Kress and Norman Fairclough’s influence can be felt throughout the NLG’S statement. Throughout Kress’s work, he has urged for a metalanguage to describe various semiotic systems, a flexible toolkit that does not put an undue burden on teachers and students (NLG 77). Also, from Kress comes the idea of design. Students are no longer merely passive receivers of information; instead, students use the semiotic resources available to them to design and redesign texts, a design-based pedagogy taking into account all the sociocultural, historical factors that go into designing. Fairclough contributes the concept of discourse and plurality of discourses in a contemporary society as well as the ways in which power is regulated through orders of discourse.

Although the NLG has become extremely influential within rhetoric and composition, I do not see the NLG’s recommendations for a metalanguage and design-based pedagogy, the “what” of multiliteracies, being taken seriously into consideration. This is probably due to the extreme paradigm shift required for these recommendations to be implemented. Instead, multimodal pedagogy has split into two camps: multimodal composition, a product-driven, technology-focused curriculum, and multimodal social semiotics, multimodality in its original sense, utilizing SFL as a metalanguage and social semiotic framework to analyze multimodal texts, the second strand being quite rare in education.

Multimodal Composition

Two surveys show the “what” of multimodal composition boiled down to the integration of technology in the classroom and the assigning of projects in lieu of traditional writing assignments. In their survey, Anderson et al. investigate multimodality as technology use in college classrooms, which software were most prevalent, access to technology, instructional approaches to integrating technology, and the types of multimodal projects teachers assigned their students. Lutkewitte’s survey of graduate teaching assistants in first-year composition similarly focuses on technology usage and the incorporation of multimodal projects in the classroom. This is not to say that technology integration and projects are not essential. Giving students access to technology and software helps them become upwardly mobile members of the creative class, but educators need to frame the production of multimedia from a design-based perspective.

Indeed, studies such as these show there is much confusion over what multimodality even means. Claire Lauer brings up the confusion over terminology and comes to the conclusion that the term “multimodality” is used in academic settings to refer to a number of different things, mostly the use of technology in the classroom, and that “multimedia” is instead used more frequently in popular contexts outside academia (26).

Multimodal composition, as remediation, is often utilized to give basic writers non-traditional project options that connect with their personal lives, while not being overly demanding from a traditional literacy perspective. The remedial view of multimodal composition definitely differs from the NLG’s original contention that students need explicit instruction in a variety of literacies to become empowered members of privileged discourse communities. “The NCTE Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies” echoes this idea of remediation, the idea that students from impoverished backgrounds without access to literacy benefit from the integration of technology and projects. Yet, this quick fix does not address the greater need for critical literacies, especially among students from impoverished backgrounds.

Others researchers in new media and digital rhetoric have applied rhetorical and critical lenses to multimodality, using ethos, pathos, and logos, as well as feminism, postcolonialism, and cultural studies. Although these lenses are crucial, they do not provide a method for systematically analyzing various semiotics systems.

The “How” of Multimodal Pedagogy

Luckily, there has already been several decades of research into multimodality within SFL and social semiotics. The main question here is not what we do with technology, but how we analyze it. I have always found the reasoning behind the integration of multimodal projects in the classroom somewhat counterintuitive, as though using technologies helps students understand technologies’ sociocultural ramifications. For instance, it would seem absurd to require students to write a book in order to understand literature. As screen-based texts have become the dominant form of writing and communication, there is a greater need for teachers and students to be able to describe, analyze, and critique multimodal texts.

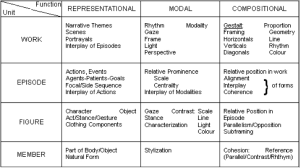

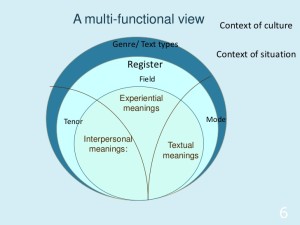

Multimodality is based in the work of Michael Halliday. Halliday made an important distinction, shifting the conceptualization of human experience from knowledge to meaning (1). This semantic shift from knowledge to meaning enables researchers to study meaning-making in various semiotic systems. O’Toole was the first researcher to apply Halliday’s functional language to an analysis of art in The Language of Displayed Art. In the semiotic toolkit O’Toole created, meaning is viewed from three perspectives (the representational, modal, and compositional) and four ranks of depth (see fig. 1). Next, Kress and van Leeuwen adapted this metalanguage for screen-based texts. Since then, researchers have been developing specialized metalanguages for many fields, including children’s books, websites, film, television, commercials.

Figure 1, O’Toole’s Semiotic Toolkit

One of the biggest questions to come out of this research is intersemiosis, how multiple modes, such as the juxtaposition of text and video, combine to make meaning. Jay Lemke has even researched, what I guess you would call trans-semiosis, how the meaning-making systems of large, transmedia franchises such as Harry Potter span multiple platforms – books, movies, toys, videogames, electronic spaces, etc (581).

A social semiotic approach to multimodality is useful for several reasons. It gives teachers and students a metalanguage and functional toolkit for analyzing multimodal texts. This toolkit is recognized by researchers in fields from all around the world, is not overly burdensome for teachers and students to learn, especially if the metalanguage is introduced in primary grades, and applies to many literacies – print texts, the Internet, film, and sound. The research I have done using a metalanguage and multimodal toolkit has led to some surprising results. Students that learn the metalanguage raise metawareness, pay more attention to detail, become better critical analysts, and boost confidence. There will certainly continue to be ongoing debates as to what multimodality, new media, and digital rhetoric is, but in the meantime I am interested in finding answers to the questions of how. How do we integrate a metalanguage into education that spans mediums and promotes literacy and critical analysis?

Works Cited

Anderson, Daniel, et al. “Integrating Multimodality into Composition Curricula: Survey Methodology and Results from a CCCC Research Grant.” Composition Studies 34.2 (2006): 59-83. Web.

Halliday, M. A. K., and Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. Construing Experience through Meaning: A Language-based Approach to Cognition. London: Continuum, 1999. Print.

Lemke, Jay. “Transmedia Traversals: Marketing Media and Identity.”

Lauer, Claire. “Contending with Terms: ‘Multmodal’ and ‘Multimedia’ in the Academic and Public Spheres.” Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook. Ed. Claire Lutkewitte. Boston: Beford/St. Martin’s, 2014. 22-41. Print.

Lutkewitte, Claire. Multimodality Is…: A Survey Investigating How Graduate TeachingAssistants and Instructors Teach Multimodal Assignments in First-YearComposition Courses. Print.

NCTE. “NCTE Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies.” Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook. Ed. Claire Lutkewitte. Boston/New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2014. 17-21. Print.

New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review 66.1 (1996): 60-93. Web.

O’Toole, Michael. The Language of Displayed Art. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson UP, 1994. Print.